The runway, the pilot informed us, is “congested.” Planes lined up before and after us. As we turn a corner, I can see the plane ahead of us take off. I see where the concrete turns black. That must be the spot where plane after plane reaches speed. But what paints the tarmac black? Is it tires? Or is it exhaust burning the pavement? My bike ride is finished. I am going home.

The Portland airport is near the Columbia River, where Lewis and Clark rode towards what is now Seaside where they built their fort for the final winter before going home. I rode by the airport on my trip as well, on a bike path a hundred feet above the river. Down on a small river beach, a houseless person was cooking something on a campfire. I rode by, above, singing snippets from the Crosby, Stills and Nash song, “Wooden Ships.”

“Say can I have some of your purple berries.

Yes I’ve been eating them for 6 or 7 months now

Haven’t got sick once.

Probably keep us both alive.”

I don’t think anyone heard me.

That’s most of the song, for me. I remember the chorus, but the rest of the song is gone. So if I feel like singing, and I don’t want to go crazy singing the same thing over and over, I’ve got to switch songs. A verse from “Hey Jude” here, a snippet of “Singing in the Rain” there. “Operator” by Jim Croce.

All I have of that one is one line, “Operator. Can you help me place this call?”

“Operator” and “Wooden Ships” go together well, I think. They both work as sing-speak songs. They ride the line between poetry and prose. When I write poetry, I try to avoid words like “operator,” because it sounds clunky to me, and because it is so flat and reductive. But a lyricist thinks differently. To the lyricist, a word like “operator” is a challenge to overcome. Croce goes all in with the word. It’s the first word in the song. He hears and exploits the stress on the third syllable, op-er-A-tor, amplifying the pleading tone in his voice and giving the song its hook.

“Wooden Ships” is the same way. “Say can I have some of those purple berries” is barely melodic at all. There’s just enough music there to make it singable-- no more, no less.

Most of the time, we try to push the prosaic out to the edges. Classic landscape photographers like Ansel Adams worked diligently to exclude power lines from their compositions. When I ride into cities and towns, the first things I usually see are industrial buildings, storage units, silos, airports. We fine people for leaving their old cars on their lawns to rust away in public instead of hiding them behind a fence in a junkyard, because they’re ugly. But sometimes it’s possible to make the utilitarian beautiful.

Bridges are beautiful, and the last few weeks of my ride were shaped by them. But before I get to that, there are some hills to climb.

July 15 46 miles, 4,400 feet elevation gain. From Heart of the Monster to Winchester

A good day, but a hard one. Half of the elevation gain was a steady 11 mile climb. The average grade was about 4.2%, but there were a couple of spots at a much steeper 10.6% grade. I’m glad I took that hill early in the morning while it was still relatively cool out. The rest of the hills were spread out through most of the day. That first hill rose up a forested area, roughly following Lawyer Creek, which was named after the Nez Perce person who signed a bad treaty with the Feds.

Nothing in my experience challenges me to “live in the moment” like taking a long, steep hill on a bicycle. I’m a weak rider. I’m not going to get up that hill through force. I’m not going to get there by racing. If I let my mind live at the faraway finish line, I will burn myself out. I can only live one cycle at a time. For me, it’s a state of deep listening: to my legs, my heart, my lungs as I prod myself and my bike for the right cadence, the right gear, the right speed to sustain the climb and the distance.

Near the top, the trees drop away and the land opens up in all directions, high, rolling hills and fields of hay and wheat. I took pictures, but, as is often the case, they are not satisfying. So many times I find myself reaching for the phone to take a snapshot, only to realize that the landscape isn’t really what I’m trying to capture. What I’m wanting to capture is the change, from shadow to light, green canopy to blue sky, gurgling creek to dry, hot earth. Photographs don’t capture that.

They also don’t capture the heat.

That night I stayed at the Winchester Lake Lodge. I met the owners, Patti and Larry. They talked about the difference between seeing yourself as an “owner” of a piece of property, vs. being “stewards” of the land. It was a nutritious conversation, and I felt refreshed after it.

July 16 45 miles, mostly downhill. From Winchester, Idaho to Clarkson, Washington.

I remember this ride from 2018. That time, I didn’t stop at Winchester, but kept going to Lewiston. I remember being exhausted when I got to Lewiston. It would have been 90 miles of riding. It is hard to imagine doing that now, even though this section is mostly downhill.

That includes a harrowing, awe-filled ride down Winchester Grade Road: a 2500 feet drop through 14 miles of ribbon, with views of golden wheat in every direction-- hill after hill of it, a harvester in the distance riding the slopes, grabbing rows of wheat at scary angles, puffing dust and smoke in its wake.

Awe can be a dangerous thing, though. The drop-offs are steep.

In Lapwai, I found the oldest historical marker I’ve seen on any of my trips: a stone tablet placed in 1946, with chiseled text about the “mountain man” William Craig cut in the shape of the state of Idaho. The sides are left rough, like the border of Idaho itself, which follows the crest of the mountains bordering Montana.

William Craig’s resume is like a sketch of the history of settler domination in the West:

· First Permanent White Settler in Idaho. 1840

· First Nex Perce Indian Agent. 1848

· Interpreter at Walla Walla Flathead and Blackfoot Councils. 1855

· Lieutenant Colonel, Washington Territory Volunteers, Indian Wars 1856

It was already hot when I got to Lewiston, and I stopped at a park to refill my water bottles and get my bearings. I met a young, unhoused woman who was rinsing her face and arms at a water fountain. She said she was getting ready for a court date--her first as an adult. I wished her well and gave her a power bar, which she took somewhat skeptically.

Clarkston is just across the river, out of Idaho and into Washington. I had to wait a couple of hours before the hotel room was available. By the time the room was ready, it was 105 degrees.

July 17. I took the day off, and for the next week or so, I took shorter rides early in the morning. I didn’t feel safe riding in hair dryer weather.

July 18. 30 miles, 2,000 feet elevation gain from Clarkston to Pomeroy.

July 19. 36 miles, 1480 feet elevation gain from Pomeroy to Dayton.

July 20. 32 miles, minimal elevation gain from Dayton To Walla Walla.

July 21. 31 miles, minimal climbing from Walla Walla to Cameo Heights Mansion near Touchet.

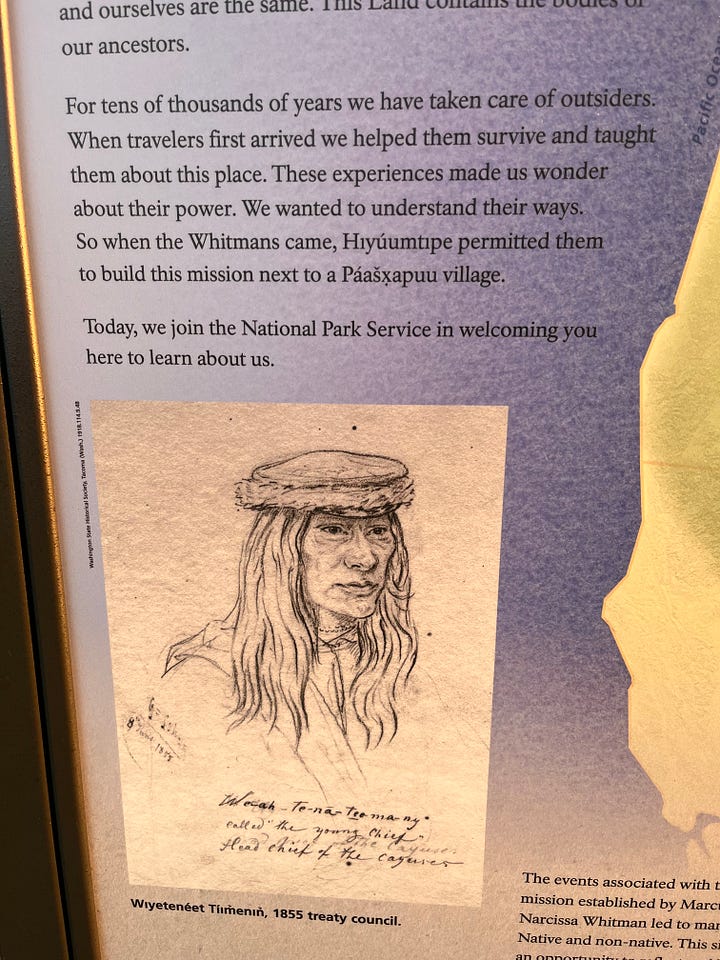

The Whitman Mission was an important stopping point on the Oregon Trail in the 1840s. The influx of people brought a measles epidemic, and a group of Cayuse killed missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and others on November 29, 1847.

July 22. Touchet to Umatilla 33 miles, 1000 feet elevation.

July 23. Umatilla to Roosevelt State Park. 52 miles, 1400 feet elevation

The morning was very windy. The wind calmed down as I turned with the Columbia River.

I met a family from Vancouver, Canada who came to this park every year for the wind-surfing. The wife and daughter took turns with a hydrofoil board. It was very hot. I picked a nice spot to set up my tent, but the camp host said I would have to move. A sprinkler system was going to go on at 11 at night. He said I coiuld camp near the beach, which was in the sun at that point.

July 24. Roosevelt to Briggs Junction. 36 miles, 1800 feet elevation gain. Another hot day

Hitched a ride to get over a narrow bridge.

July 25.

Briggs Junction to The Dalles. 30 miles. 1800 feet elevation

I left before light so I could cross the bridge without any traffic. I think it was a 2 mile climb back to the highway, then a short limb over a hill after that. I crossed back over to Oregon at The Dalles. There was a brief moment when I smelled smoke and felt it sting the back of my throat. But that passes quickly.

July 26. 28 miles. 1400 feet elevation

The Dalles to Hood River. I had to backtrack up the hill to the Washington side, because I heard that the town of Mosier had been evacuated due to the Microwave Tower Fire. So I went back over The Dalles Bridge, rode to Hood River, then hitched a ride back across another narrow bridge to Oregon.

July 27. Hood River to Cascade Locks 20 miles, 1400 feet.

July 28 Day off

July 29. Cascade Locks to Portland. 41 miles, 2300 feet

July 30 Portland to St. Helens. 43 miles, 1200 feet

July 31 St. Helens to Clatskanie 37 miles, 1500 feet.

Nice 3 mile climb up a back road.

August 1. 36 miles , 1900 feet. Clatskanie to Astoria

And that’s it. The Lewis and Clark route actually goes another 20 miles to Seaside, but I didn’t have time to do that. I met up with Melissa for just an all-too-brief time at the Maritime Museum in Astoria. It took a couple of days to wrap things up before taking a bus back to Portland, then this plane back home to Alaska. I’m having trouble wrapping the three thousand mile bike ride into a neat package. Perhaps later down the road I can summarize the experience. Right now, all I have are boring words, like “rich,” “varied,” “spiritual,” “refreshing.”

"I’m having trouble wrapping the three thousand mile bike ride into a neat package." No kidding!

Thank you for sharing this amazing and varied experience with us!

I'm glad you are home safely.....

Love, Larri

A great retelling of an incredible experience. You’re a unique cyclist.